SEEN

DONDI

BLADE

Naturally not everyone considered this new wave of activity a pleasant art form, in fact many became incredibly frustrated and even disgusted by the sight of trains covered top to bottom in brightly coloured letters. Of course, as the number of writers went up, the amount of available painting space went down and many true and dedicated writers had to compete with inexperienced and untalented fly-by-nighters who were desperate to get in on the act, effectively ruining many train lines with childish scribblings and crossing-outs of better "pieces". The authorities came under pressure to curb what the majority of the public saw as nuisance, despite the rather whimsical interest of the New York art scene.

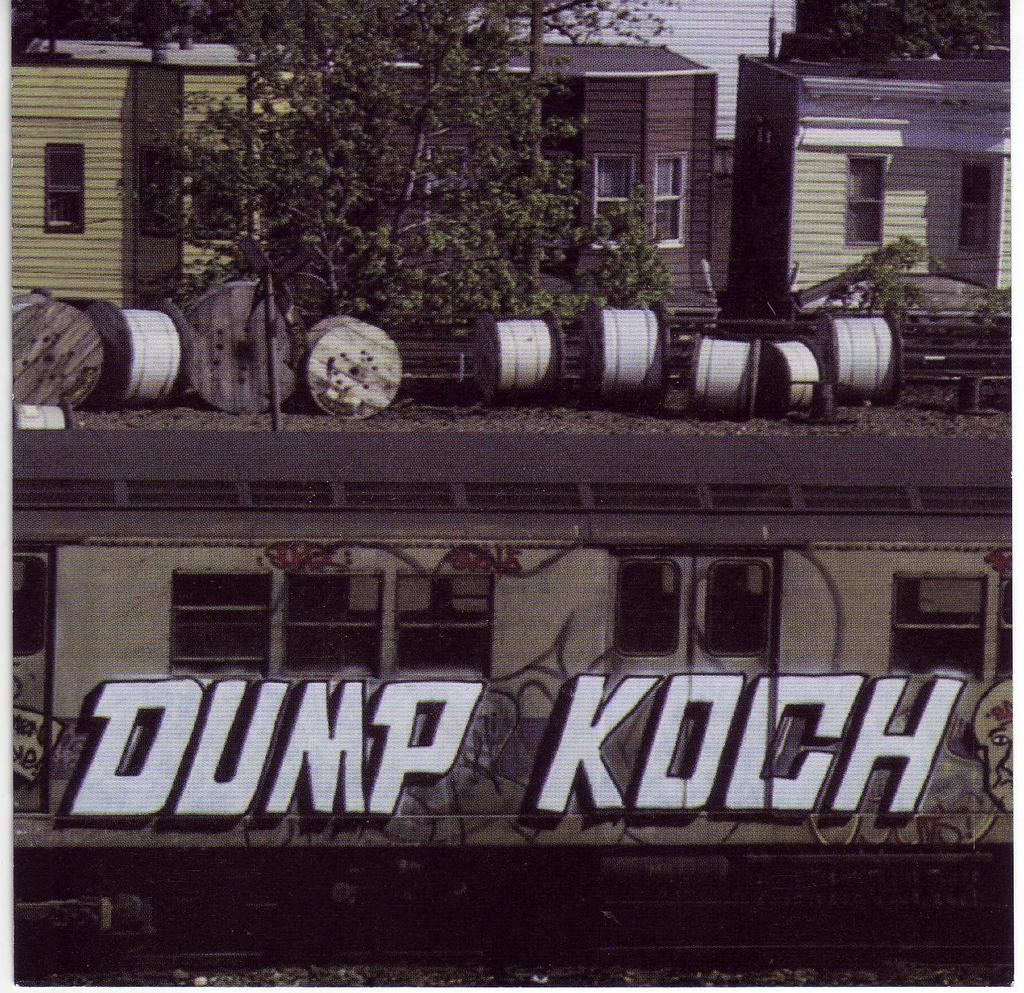

In the early eighties, Mayor Koch declared a "war on graffiti" and immediately set about an aggressive clamp down on the city's flowering subculture. He set up what came to be known as the "buff", a process of washing the trains with a special chemical spray which ironically didn't always eradicate the paint sometimes merely fading it and leaving the carriages looking more ragged and unpleasant than before. Regardless, hundreds if not thousands of pieces were "buffed" and the train yards which had previously been easy to access, became veritable fortresses protected by barbed wire, round the clock security and snarling guard dogs. This era marked the beginning of the end and is captured poignantly in Henry Chalfant's 1982 documentary, Style Wars.

Despite retaliation from the writers themselves as well as many ingenious tactics they employed to continue accessing the train yards, painted carriages declined steadily and come 1988, they virtually stopped running all together. On the surface it seemed that Mayor Koch had won his war, however, it wasn't enough to stop the art form spreading explosively all over the globe. The eighties saw graffiti infect

almost every corner of the urbanised world, including Great Britain which in recent years has mounted its very own "war on graffiti".

almost every corner of the urbanised world, including Great Britain which in recent years has mounted its very own "war on graffiti".DUMP KOCH by SPIN

1 comment:

i love,...salut!

Post a Comment